Facebook and eCommerce domination Part 3/3— Gee, Brain. What are we going to do tonight?

Jun 21, 2020

In the last article, we explored the human habit of Signaling and how it put FB/IG at the apex of the social world.

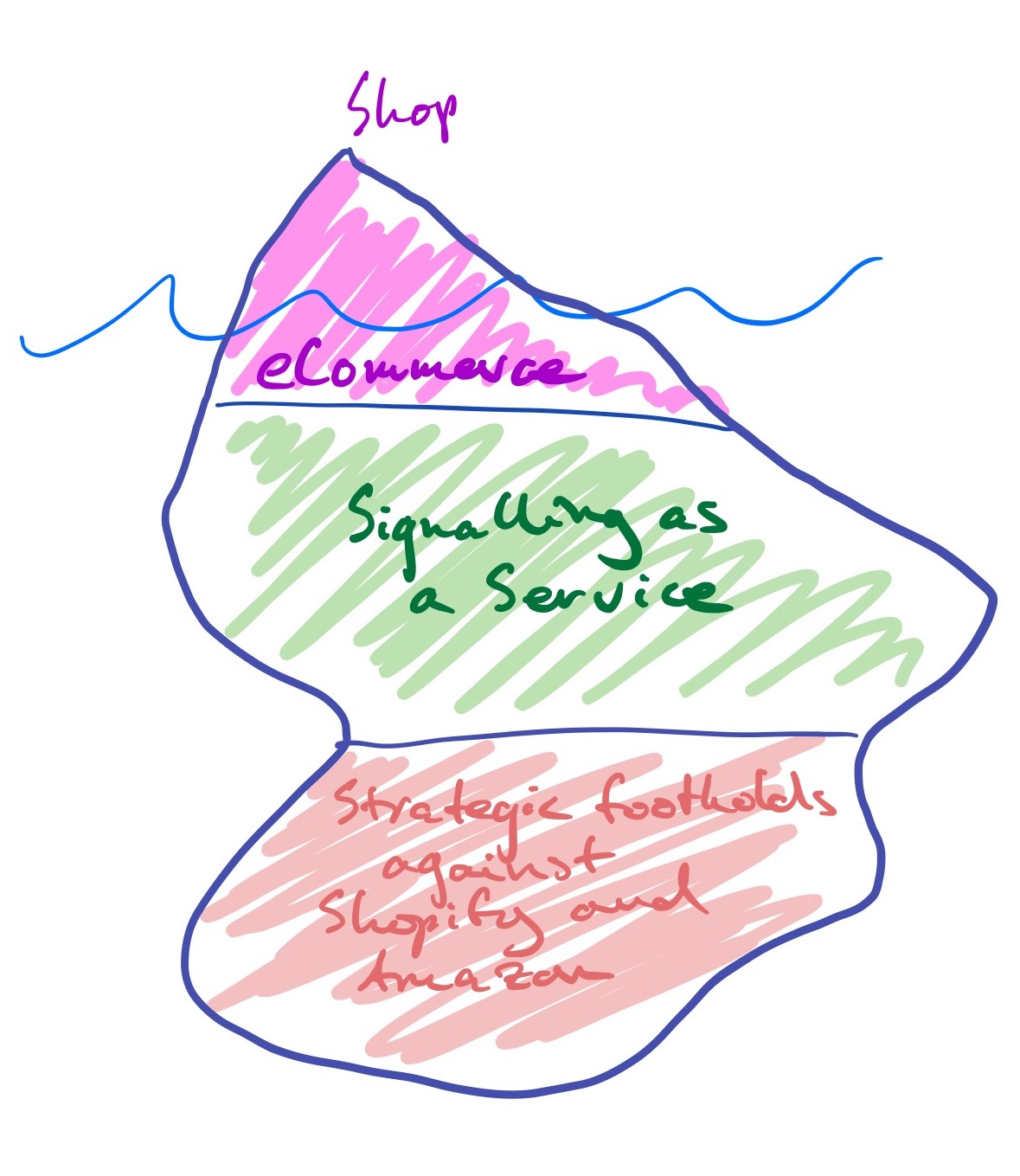

In this article, we’re going to be talking about the bottom portion of the Facebook Iceberg

Thesis of this article:

Facebook’s strategic goal, more than revenue from commissions, adoption, or retention, is to convert businesses to be 100% integrated with Facebook. A failure mode of Shops is if sellers still keep their Shopify-Squarespace shops and Amazon FBA hookups open

I’ve been reading Facebook: The Inside Story by Steven Levy. As I read more, the stronger the feeling I get of yearning. Facebook is a company of yearning: to connect the world, to grow at all costs, to creep and transgress past previous boundaries (both implied and explicit). The feeling I get is that Facebook wants to take over the world.

This is not your grandparent’s product launch

Usually when you launch a product, you look at usage and retention rates. If those are good and high and BIG, you should expect to see revenue growth. However, according to the Facebook Help Center, there don’t appear to be any additional fees associated with Shops.

Facebook’s vice president of ads Dan Levy said that while the company will charge “small fees” on each purchase, the real monetization will come from driving more advertising.

This leads me to believe that the goal of Shops is to carve out strategic footholds against competitors like Shopify and Amazon. Facebook is making two strategic moves here: 1) Commoditizing their complements and 2) Strengthening their network effect

Commoditizing your complements creates a desert of profitability around you and prevent competitors from sidling up next to you

Complements are items that are bought together:

Gas and cars

Babysitters and expensive dinners

Flights and hotel rooms

“All else being equal, demand for a product increases when the prices of its complements decrease.”. For example, if gas prices go down, truck sales go up (unfortunately). If flights get cheap, hotel rooms see an increase in demand

Smart companies look to decrease the price of their complements, so that more people can access their product. As it were, this is why Facebook built Internet.org: the more people who are on the Internet, the more people that can use Facebook

This also has a nice side effect of “creating a desert of profitability around you”, where if a company wants to get alongside you, they have to compete with free. Take Google Docs, for example: for a company to try to make inroads to Enterprise document management, they’re eventually going to run into competition with one of GSuite’s “good enough”, free bundled offerings (Gmail, Chrome, Drive, Docs, etc)

It’s notable that this commoditized complement is, essentially, Shopify: Facebook is essentially saying “oh, that other Billion-dollar company over there? Well, we made it free”

Identify and own Network Effects

You typically see Network Effects in Marketplace products—where there are two (or more) sides that the Product brings together. The revenume model of Marketplaces tends to be based on a commission basis: for a successful match, the Marketplace gets a %. Think about eBay, Airbnb, and Uber

One thing we talk about in great detail with Marketplaces is Supply and Demand

For eBay: Sellers and Buyers are Supply and Demand, respectively

For Airbnb: Hosts and Guests

For Uber: Drivers and Riders

Network Effects translate to Economies of Scale: The larger the company, the cheaper and easier it is to acquire users. For eBay, those first few Sellers were insanely hard to convince to join the Marketplace: “Excuse me, what? You want me to send this $1000 camera in the mail to someone I’ve never met? And use this PayPal thing?” But the later Sellers were easy to get

A marker of Network Effects is that the system is more useful as the number of users on the system grow. For example, Facebook would be pretty useless if you didn’t have anybody to connect to

Here’s Uber’s Network Effect (among many):

If the number of drivers in the system increases, then wait times (and costs) for riders decrease, and riders are more likely to join. If ridership increases, then drivers will have less downtime, and drivers are more likely to join

Dating sites have to be aware of Network Effects:

If one gender greatly outnumbers the other, people start to leave the Marketplace. Tinder, OkCupid, and Raya have to manage this market balancing delicately, just as any bar in New York does at the door (looking at you, Le Bain)

The important thing to take from this section is that if you are subject to Network Effects, you need to do some extra work to entice at least one side to enter the Marketplace. Once they’re in there, their presence will attract the other side. Airbnb solicited Hosts first by replying to Craigslist ads. Uber just straight-up bought Drivers with Referral Bonuses

Putting it all together- Facebook’s Network Effect play is based around making shopping on mobile easier to entice Shoppers, whose presence on the Marketplace will attract Merchants

In the US, mobile purchasing (colloquially called, eye-rollingly, mcommerce) has historically been weak compared to desktop. China is MUCH more advanced when it comes to shopping on phones

Some of the reasons for this:

Large retailers have just started investing in ecommerce desktop websites, so most mobile websites are just bad ports from the desktop site. Nobody wants to buy this way

Purchasing online comes with a LOT of comparison shopping. More than you would do in the store. It’s hard to comparison shop and surf multiple tabs on your phone

You have to type in a lot of information when you do decide you want to buy: Address, credit card, etc. It’s harder to do that on a phone than on a keyboard

Facebook is driving down to one-click shopping

One thing that mcommerce gurus work to minimize is the number of steps in the conversion flow. Studies show: the longer the checkout flow, the lower the conversion

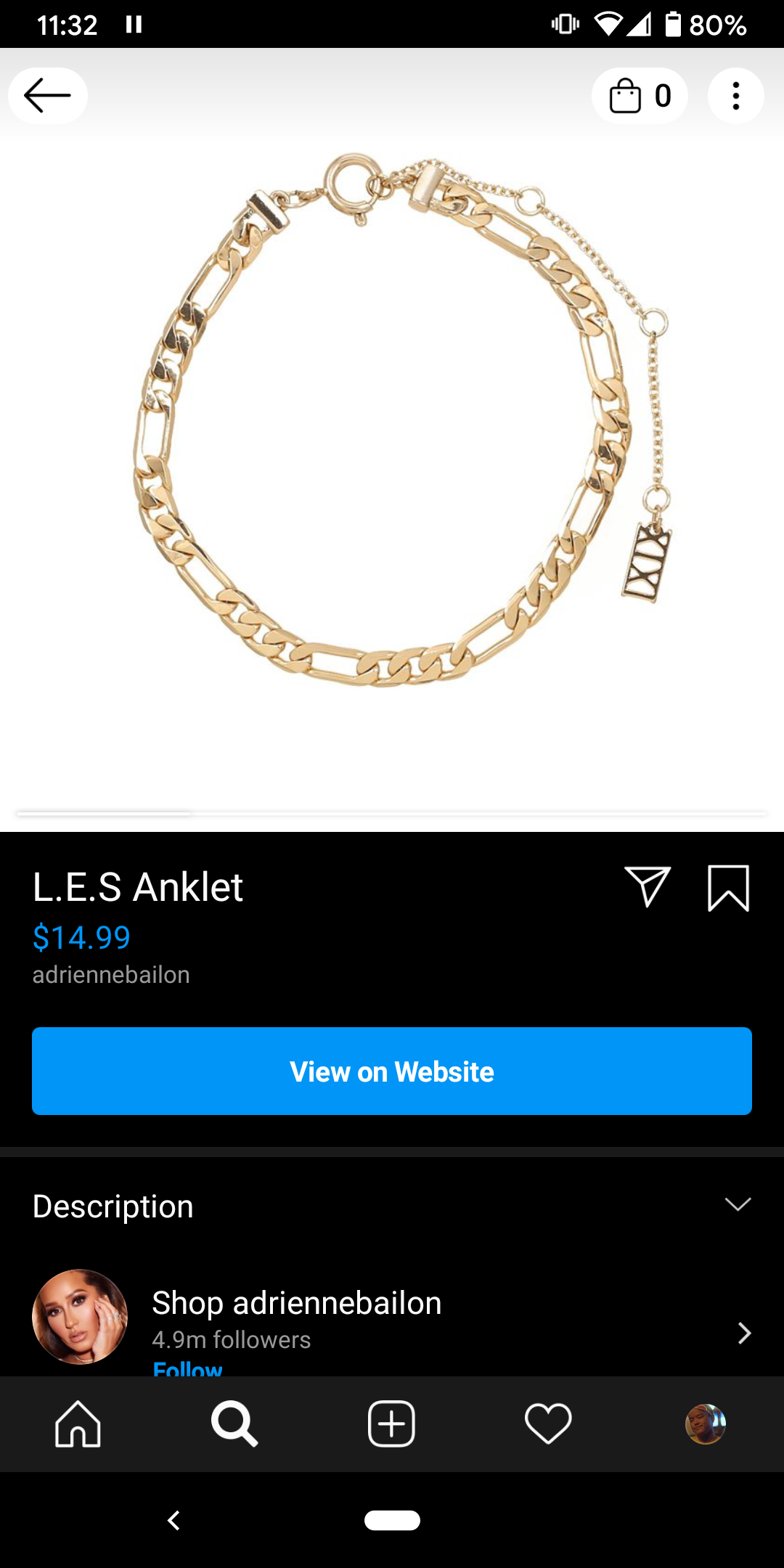

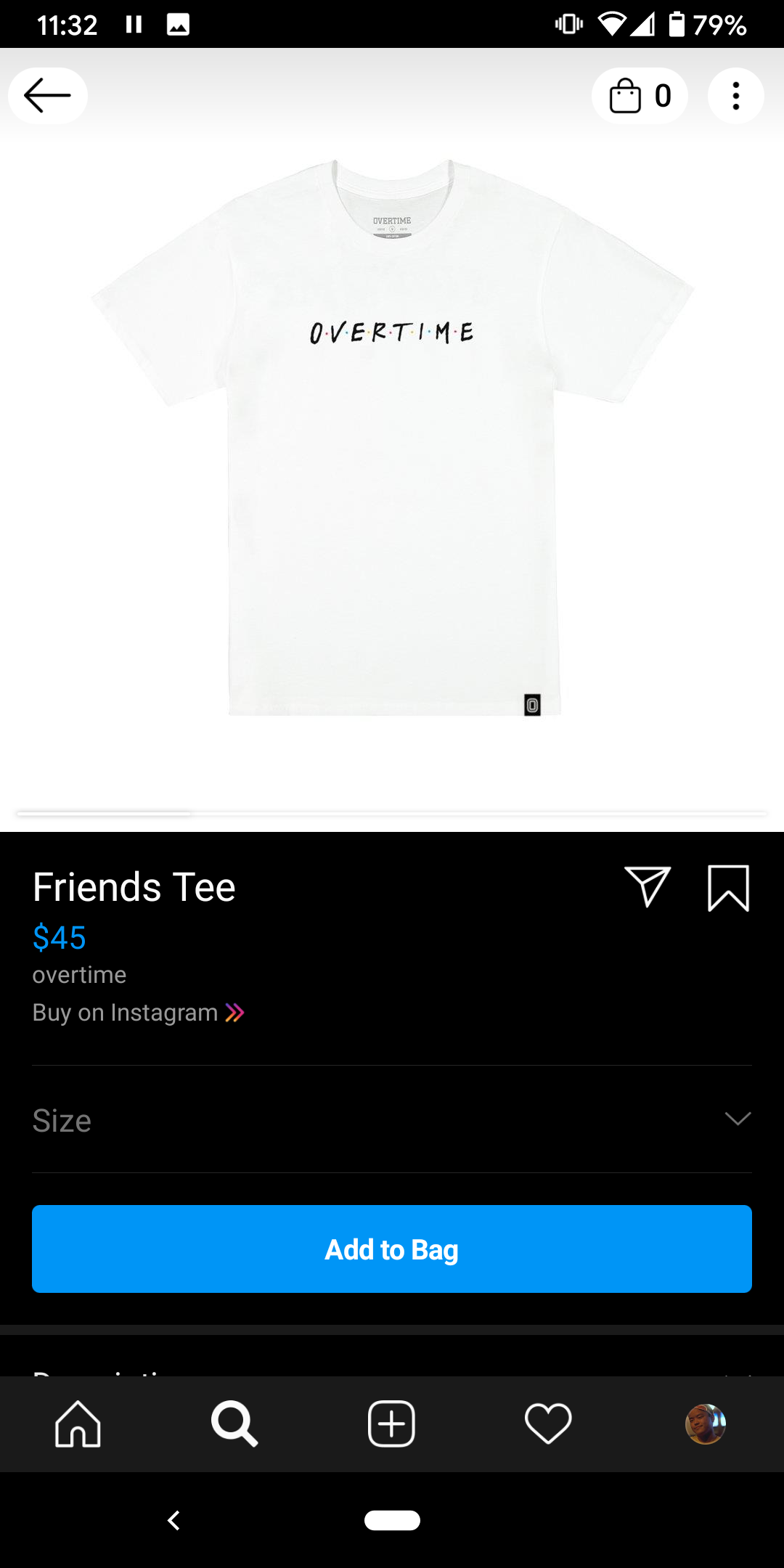

Take a look at these two screenshots.

The first is an Instagram Seller that is NOT on Shops

The second is an Instagram Seller that has opted in to Shops

The difference is subtle, but important.

In the first, your cart/bag is elsewhere. In the second, your cart/bag is with you on IG. You never have to leave the app. You never have to suffer an unoptimized checkout flow. Instagram is your new family now. It reminds me of another one-click UX that someone patented in 1999

Lest we forget the capital-D-Data

As they’ve reminded us so clearly, on multiple occasions, Facebook is a Data company, and we oughtn’t forget that

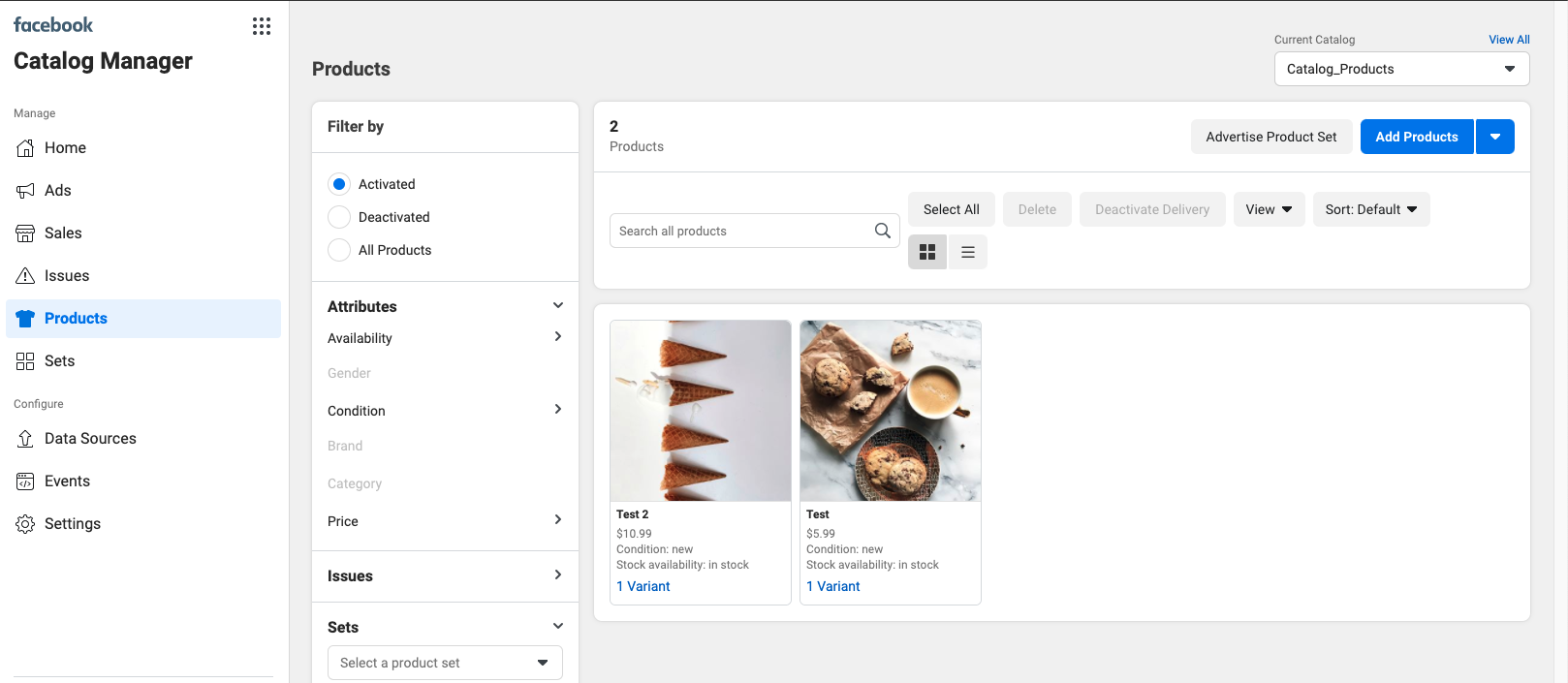

More Shoppers in the Marketplace gives Facebook more data on Shopper preferences, sure. But the Marketplace has two users: to use Shops, Merchants upload Products into the Catalog Manager. In the below screenshot you can see some of the attributes and metadata that Facebook asks for: Gender, Brand, and Category

This starts spinning up the Network Effect:

The more products that are uploaded to Facebook Shops, the more effective it becomes at curating products for consumers, which brings on more Shoppers. This, in turn, brings in more Merchants, which provides more data for curation

In summary

Facebook is going for eCommerce domination. They’re not looking to preserve a sliver of the market, they’re looking to take the whole damn thing

They’ll accomplish this by making free tools for merchants that are subsidized by the Ads cash cow

Because Facebook and Instagram (FB/IG) already own consumer eyes (thanks to the human desire of signaling), it makes sense for merchants to meet those consumers on FB/IG

Over time, as the number of merchants on Shop grows, so, too, does the Network Effect: more consumers shop on FB/IG, the shopping experience becomes easier and faster, and more merchants join the platform. The whole time, everybody in this system is throwing off data for Facebook to vacuum up and use to make the system even more efficient